Winner of the HUC-JIR Lorraine Helman Rubin Memorial Prize for Scholarly Writing

Introduction

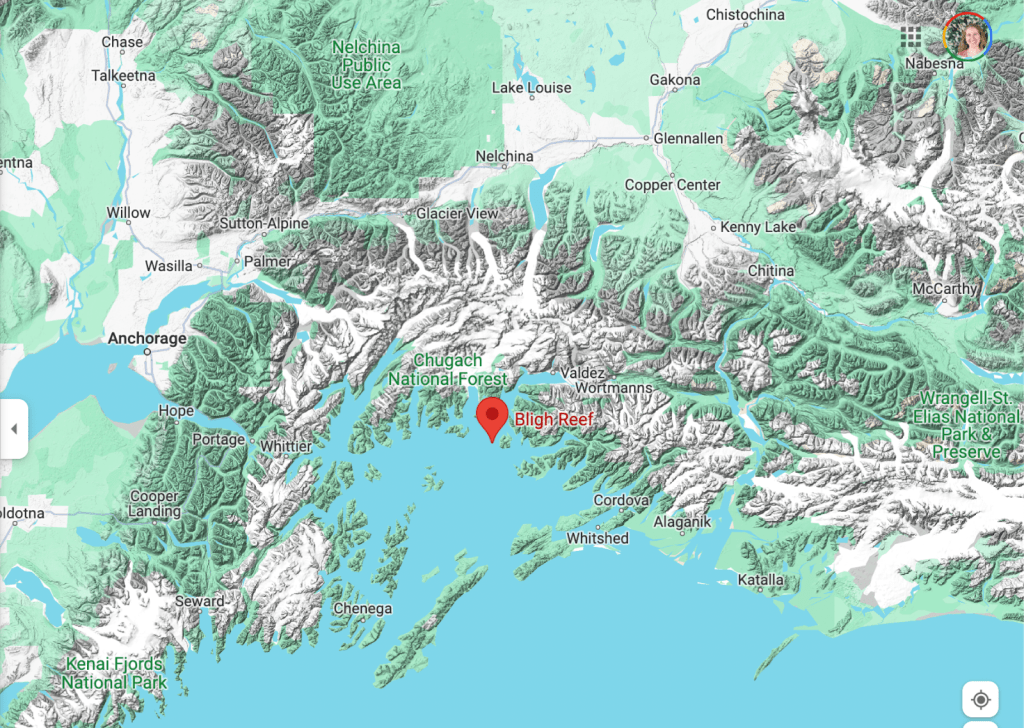

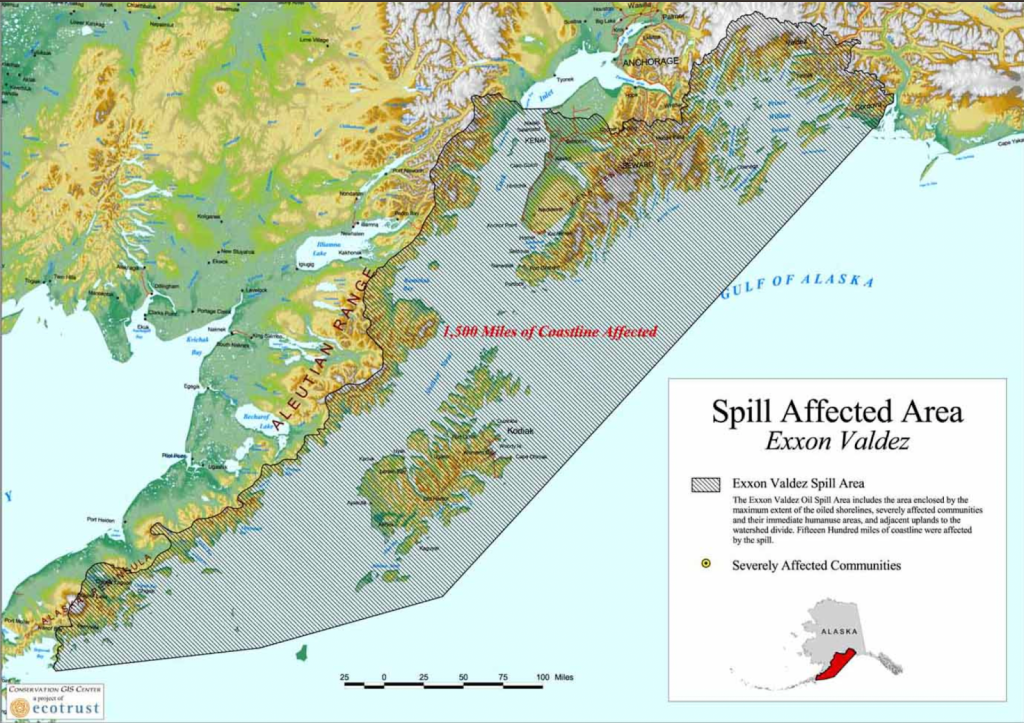

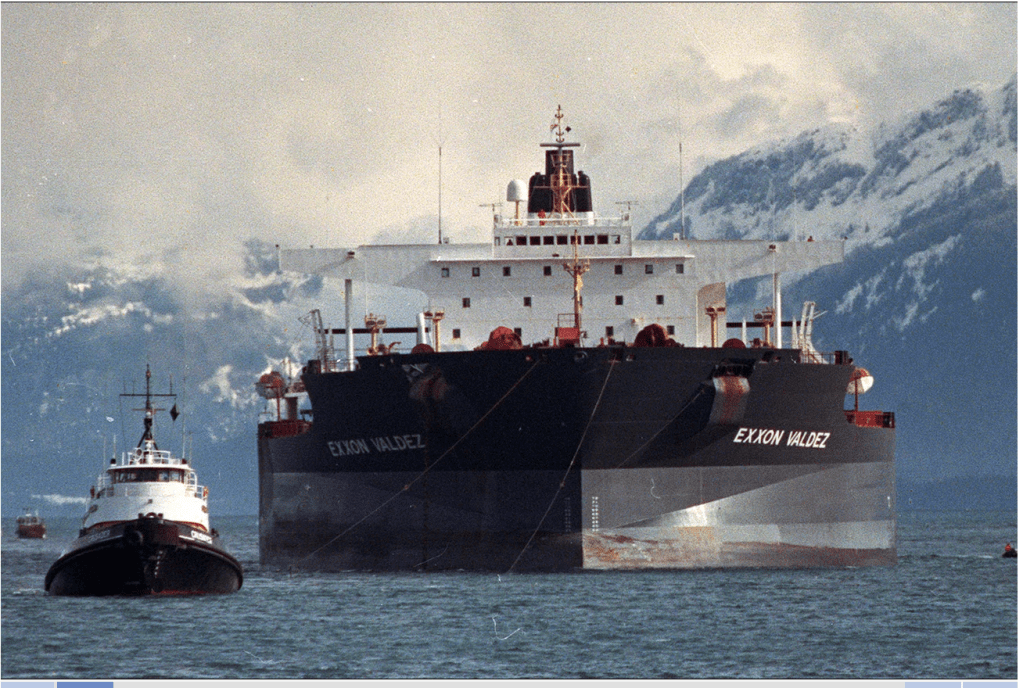

On March 24, 1989, just after midnight, the Exxon Valdez oil tanker ran aground on Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound, an inlet in the Gulf of Alaska, on its way from Valdez, Alaska to California. Due to delayed efforts to contain the spill and stormy conditions, 11 million gallons of North Slope crude oil dispersed into the waters eventually polluting 1,300 miles of shoreline and adjacent waters. This was the largest environmental disaster in US history up to that point in time. At risk was “the delicate food chain that supports Prince William Sound’s commercial fishing industry… ten million migratory shore birds and waterfowl, hundreds of sea otters, dozens of other species, such as harbor porpoises and sea lions, and several varieties of whales.” In the end an estimated 250,000 seabirds, 2,800 sea otters, 300 harbor seals, 250 bald eagles, as many as 22 killer whales, billions of salmon and herring eggs were killed. More than 25 years after the spill the killer whale population, the herring population (once a life source for the region), several bird species had not recovered, and pools of oil were still found under and between rocks along the shore line.

In addition to the devastating environmental impacts, local communities supported by commercial and subsistence fishing were similarly impacted. The town of Cordova, for instance, a small fishing village, was especially hard hit. As NPR reported in 2014: “the disaster upended life in Cordova for years. Fishermen were docked. Businesses went bankrupt. Drug and alcohol abuse went up, along with reports of domestic violence and depression. The mayor committed suicide. Those paid by Exxon to work the cleanup were jealously labeled ‘spillionaires.’” Many fishermen, including Alaska Natives whose families had fished the waters of Prince William Sound for generations and generations, were forced to give up their way of life forever. Additionally, over time it became clear that there were negative long term health impacts on clean up workers who were largely people in financial straits due to the spill with few other options.

Due to the scale and scope of the damage done by the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill, the response was massive, drawn out, and multi-pronged. There were several levels and timelines of responses that ranged from clean up efforts in the immediate aftermath of the spill to litigation that dragged on for decades. Actors involved in the response ranged from individual clean up crews on the ground in Alaska, to oil company executives, all the way up to the Supreme Court of the United States.

In the aftermath of the spill, multiple guilty parties were found. First there was the ship captain, Joseph Hazelwood, who had allegedly been drinking the night the ship ran aground at Bligh Reef. Next there was the oil company Exxon (now ExxonMobil) that did not have adequate safeguards on their vessels against events like this, and had a company culture that did not value safety and worker protection. The US Coast Guard was similarly found guilty in that they were not adequately prepared to handle a spill of this magnitude and were not properly regulating sea traffic in and out of Prince William Sound. The US Government even took actions that expressed a certain amount of guilt around not adequately regulating oil shipping in US waters. In order to evaluate the ways in which each “guilty” party addressed their role in the spill and how each understood the process of atonement, reconciliation, and restitution, we will look at each of their words and behavior in the aftermath of the spill.

Captain John Hazelwood

Exxon initially blamed Captain John Hazelwood for running aground on Bligh Reef, citing that he had been drinking heavily the night before and was therefore not in proper control of the ship. He was immediately terminated and never sailed again. In 1990 Hazelwood was charged with criminal mischief, reckless endangerment, and piloting a vessel while intoxicated. 21 witnesses testified that he did not appear to be under the influence at the time of the crash. He was eventually cleared of all charges. He was convicted of misdemeanor negligent discharge of oil and sentenced to community service in Anchorage. Although Exxon blamed Hazelwood, Hazelwood accused the company of making him a scapegoat. In later investigations it was found that overwork and exhaustion caused by a toxic corporate culture, and insufficient, outdated, and broken radar technology that Exxon had not updated or fixed in years ultimately caused the crash on Bligh Reef.

Although likely a victim of corporate negligence and scapegoating, Hazelwood ultimately atoned for his role in the spill. Twenty years after the spill, Hazelwood offered a heartfelt apology in a book published with stories reflecting on the spill. “I was the captain of a ship that ran aground and caused a horrendous amount of damage. I’ve got to be responsible for that,” he said. “I would like to offer an apology, a very heartfelt apology, to the people of Alaska for the damage caused by the grounding of a ship that I was in command of.” This apology shows that while Hazelwood may not have been ultimately responsible for the scale of the damage, as captain of the boat he still felt a certain amount of responsibility and that no matter what, he played a role in the harm that was done. While I don’t think he went through a whole process of Maimonidean teshuvah, because in many ways he could not have due to his termination, he still verbally took responsibility for his actions and apologized to the injured parties. He had clearly spent decades reflecting on the accident and the role he had played in it and was now publicly proclaiming his guilt. People had been hurt by the results of his actions (or inaction) and he owed it to them to acknowledge their pain and take responsibility for the part he had played in it. He could not have done a full process of teshuvah because he was terminated from Exxon and never sailed again, so he could not resolve to do better in the future or act differently when confronted with the same situation. He was never given the opportunity. Perhaps it’s right that he wasn’t given the opportunity to do better in the future, but I do think it is too bad that his career and livelihood was ruined due to corporate negligence and scapegoating.

Exxon

According to what is now the ExxonMobil web page on the spill, the corporation “took immediate responsibility for the spill and [has] spent over $4.3 billion as a result of the accident, including compensatory payments, cleanup payments, settlements and fines. The company voluntarily compensated more than 11,000 Alaskans and businesses within a year of the spill.” They have additionally made major technological changes and have made worker safety a top priority for the company. All of this is prominently displayed and detailed on their website. In 2014, 25 years after the spill, NPR reported that “ExxonMobil spokesman Richard Keil says the company regrets that the incident took place. ‘Without doubt, it was a tragic event. But it’s something we have learned from, and we live those lessons each and every day.’”Additionally, according to the website the affected coastline and ecosystem was rehabilitated within three years of the spill, which is the company’s way of tacitly absolving themselves of guilt for any prolonged damage to the environment. It’s their way of saying they did their job, and now they can move on. In reality the environmental damage is ongoing, and may never fully go away. While on the surface ExxonMobil went through a process of repentance and restitution by making technical and cultural changes, and paying for the damage of the spill in both the criminal and civil realm, the reception of their actions and the messages those actions sent is much more checkered.

ExxonMobil fought a class action lawsuit for almost two decades after the spill. The lawsuit was finally resolved in 2008, when the U.S. Supreme Court slashed an initial jury award of $5 billion to $507 million, plus $470 million in interest. Prince William Sound locals were once again devastated by the pittance they received from ExxonMobil. Jim Kallandar, a fisherman and former mayor of the fishing village Cordova said that “Justice was not served. All my life, I’d been brought up to think that, you know, you get to the Supreme Court and everything is made right. People are made whole. Issues are corrected. And I’m still disappointed. I’ll never get over it.” According to the well researched, reviewed, and cited Wikipedia page on the spill:

As of December 15, 2009, Exxon had paid the entire $507.5 million in punitive damages, including lawsuit costs, plus interest, which were further distributed to thousands of plaintiffs.This amount was one-tenth of the original punitive damages, Exxon remained hugely profitable, the process of payment was drawn out over decades, and long term damage continues and is not funded by Exxon. Hence, the Exxon spill is often cited as shorthand for corporate responsibility for societal damage not being enforced adequately.

While ExxonMobil seemingly paid what it owed, the company also appears to have done the bare minimum in terms of restitution and found every available legal loophole available to avoid paying up. Despite the damages they owed not even making a dent in their profits, ExxonMobil prioritized profits over making restitution with the parties they had harmed. It is true that they mostly did what they were supposed to do, but they did it begrudgingly and in such a drawn out way that the harm they had caused was only exacerbated. I would hardly call that atonement- especially along Maimonidean lines.

Coast Guard

While the US Coast Guard was not found ultimately responsible, their lack of action in the immediate aftermath of the crash on Bligh Reef caused the damage done by the spill to be even more severe and extensive. Had the Coast Guard been on the scene even hours earlier and had the proper equipment for oil containment and response, it is likely the scale of the spill would have been much smaller. The Coast Guard did not even convene the Alaska Regional Response Team until noon on March 25, more than 36 hours after the initial crash, and on the ground response and assistance was not activated until much later, hampering any attempts to contain the rapidly spilling oil. In investigations following the spill it was found that ships were not informed that the Coast Guard was no longer tracking ships out to Bligh Reef and that the Coast Guard had not performed vessel inspections before the Exxon Valdez set sail out of the Port of Valdez. The Coast Guard did launch a massive containment and clean up effort, but it was too little too late to stop the spillage of 11 million gallons of crude oil into the pristine ocean waters of Prince William Sound.

The US Coast Guard, as far as I can tell, has never publicly taken responsibility for the role they played in the spill. They have taken steps to improve technology, strengthen regulations, and improve their disaster response infrastructure. Even though they may have not taken public responsibility and asked for forgiveness related to their role in the spill, they have clearly learned that in order to prevent further events like this from ever happening, they had to change in a serious way. Their form of atonement then is institutional change, which is certainly important. I would hardly call this teshuvah but it is certainly a process of learning and growth from past mistakes, which is a component of teshuvah. Should the Coast Guard be held liable for their inadequate response to the spill and undergo a formal process of atonement? I don’t know. It’s harder for me to blame an underfunded government agency than a gigantic oil corporation. The Coast Guard should certainly have been held responsible for their inadequate response to the spill, but in the end they are not responsible for the crash and spill itself- only how they responded to disaster.

Congress

As the governing body of the United States, which is ultimately responsible for creating the laws and regulations we live by, Congress passed the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 in direct response to the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill of 1989. As way of preventing and mitigating future oil spill disasters, and as a way of holding then Exxon and the Coast Guard to account, the Oil Pollution Act required the Coast Guard to strengthen its regulations on oil tank vessels and oil tank owners and operators, and improve communications systems between vessel captains and vessel traffic control centers. The Act also set a schedule for a gradual phase-in of double hulled ships, which provides an extra level of protection between the oil tank and the ocean. The Exxon Valdez, like most of its compatriots, was a single hull ship. Even if the Exxon Valdez had been double hulled it would not have prevented the disaster that took place on Bligh Reef, but a Coast Guard study estimates that it could have cut the amount of oil spilled by 60 percent. Finally, the Act barred any vessel that has caused a spill of more than 1 million gallons of oil in any marine area, from ever entering Prince William Sound. As a result the Exxon Valdez ship never operated in Alaskan waters again, and bounced around the world until it was finally scrapped on a beach in China in 2012.

I see the passage of the Oil Pollution Act as a form of atonement on the part of the US government. They realized that they had not done enough to protect US waters from oil pollution, and thus they took steps to rectify that. Much like a captain is responsible for his ship, so too is the US government responsible for what happens in its borders. Congress may have not had a direct hand in what transpired in Prince William Sound, but stricter regulations and policies on oil pollution containment could have prevented much of the damage that occurred along the Alaskan coastline. The steps Congress took to address the situation is certainly not teshuvah, but it is a form of taking responsibility for the part they played in the disaster and preventing further and future harm.

Conclusion

When Maimonides first wrote Hilchot Teshuvah back in the 12th Century, he undoubtedly could not have imagined giant ships carrying a yet unknown substance called “oil” in a faraway land known as “Alaska.” He couldn’t have imagined that a young rabbinical student would one day be sitting in Los Angeles using his process of teshuvah as a way to evaluate the process of atonement and restitution related to a massive human caused environmental disaster. He could not have imagined the scale of governments and multinational corporations that would one day dominate the world, and the scale of the harm they could cause. While all of this is the case, Maimonides’s Hilchot Teshuvah nonetheless offer a valuable framework through which to evaluate harm done not only by individuals but by bodies of individuals. He provides important concepts such as atonement/repentance through apology and taking responsibility, and monetary restitution. These concepts were certainly present in all guilty parties’ response to the oil spill and its aftermath.

Interestingly, forgiveness, an essential component of the teshuvah process, plays almost no role in the case of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. Forgiveness is an interpersonal process and the harm that was as a result of the oil spill was not an interpersonal affair. At the end of the day the oil spill was a result of the breakdown of systems, not individual human error directed at another individual human. While individual humans were directly impacted by the aftermath of the spill, the majority of the harm was done to the environment and to animals who can not “forgive” per say. Thus there is no party that is really able to forgive the guilty parties for what happened. What happened, happened and the only thing that can be done is to try and clean up and rehabilitate the injured environment and animal population.

By no means did any of the guilty parties involved in the oil spill go through a process of teshuvah but many did go through a process of institutional review and change, which is akin to a process of teshuvah. In the case of Captain Joseph Hazelwood, the captain of the Exxon Valdez, he could not have gone through a full process of Maimonidean teshuvah because he was stripped of his ability to change and do differently in the future through his termination from Exxon. As the only individual perpetrator in the saga of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill, he ultimately did take responsibility and seek forgiveness for his actions by giving a public heartfelt apology and acknowledgment of his culpability. Exxon, the US Coast Guard, and Congress as massive corporate bodies could not do the same thing. Each in their way showed some amount of guilt through the actions they took to rectify the situation and prevent future similar events from happening.

Was it all enough? I don’t know. I’m inclined to say no. It did not prevent a magnitudes larger oil spill from happening in 2010 with BP’s Deepwater Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico, and its attendant environmental, economic, and social devastation. It does show though, that in the case of massive bodies that have the capability to inflict untold harm on the world, the public must be vigilant in holding them to account when they inevitably mess up. By nature, large and unwieldy institutions are not going to fess up or part with their power easily. Atonement requires vulnerability and vulnerability requires giving up some amount of power. No large entity made of human beings is going to do this willingly, and so it is on people of conscience to stand up and force corporate bodies to make things right when they do wrong.

Bibliography

Griffin, Drew. 2010. Review of Critics Call Valdez Cleanup a Warning for Gulf Workers. Cnn.com. CNN. July 10, 2010. http://edition.cnn.com/2010/US/07/07/oil.spill.valdez.workers/.

Meyer, Bill. 2009. Review of Captain of Exxon Valdez Offers “Heartfelt Apology” for ’89 Oil Spill in Alaska’s Prince William Sound. Cleveland.com. Cleveland.com. March 6, 2009. https://www.cleveland.com/nation/2009/03/captain_of_exxon_valdez_offers.html.

NOAA. 2020. “Exxon Valdez | Oil Spills | Damage Assessment, Remediation, and Restoration Program.” Darrp.noaa.gov. August 17, 2020. https://darrp.noaa.gov/oil-spills/exxon-valdez.

NPR.org. n.d. “25 Years after Spill, Alaska Town Struggles Back from ‘Dead Zone.’” https://www.npr.org/2014/03/24/292411071/25-years-after-spill-alaska-town-struggles-back-from-dead-zone.

Review of Details about the Accident. 1990. Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council. State of Alaska. February 1990. https://evostc.state.ak.us/oil-spill-facts/details-about-the-accident/.

Review of Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. n.d. Wikipedia.com. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exxon_Valdez_oil_spill#cite_note-clv-15.

US EPA, OLEM. 2013. “Exxon Valdez Spill Profile.” Www.epa.gov. June 4, 2013. http://www.epa.gov/emergency-response/exxon-valdez-spill-profile.

Leave a comment